In a Practice Rut? Drop it. Go Dancing.

Well, it’s been a while since I’ve gotten bloggy or updated the site at all. To be honest, it’s also been a few months since I’ve been in serious practice mode. The gig schedule has been light as well. And for the first time, I couldn’t be happier about it. What gives? To tell the truth, I needed to step back. It’s not you, it’s me. As a professional musician, or any creative type really, I think it’s healthy, crucial in fact, to just drop everything and take a solid break. So I’ve done that. I’ve been teaching lots and playing the odd gig but that’s about it. I think the primary cause of burnout for creatives is the inability to truly switch it off. We are always mulling over the next arrangement or performance. For many of us, the wheel churns as we wake, do dishes, fall asleep, or worse, during a date or chat with a friend. But as them zennists like to say: “when you eat, eat. When you sleep, sleep.” It’s all so easy to read in a cutesy little blog. So tricky to put into daily practice.

Well, it’s been a while since I’ve gotten bloggy or updated the site at all. To be honest, it’s also been a few months since I’ve been in serious practice mode. The gig schedule has been light as well. And for the first time, I couldn’t be happier about it. What gives? To tell the truth, I needed to step back. It’s not you, it’s me. As a professional musician, or any creative type really, I think it’s healthy, crucial in fact, to just drop everything and take a solid break. So I’ve done that. I’ve been teaching lots and playing the odd gig but that’s about it. I think the primary cause of burnout for creatives is the inability to truly switch it off. We are always mulling over the next arrangement or performance. For many of us, the wheel churns as we wake, do dishes, fall asleep, or worse, during a date or chat with a friend. But as them zennists like to say: “when you eat, eat. When you sleep, sleep.” It’s all so easy to read in a cutesy little blog. So tricky to put into daily practice.

But as it turns out, my break wasn’t a break at all. When you give the muses some real room to do their thing? Their thing they do. Two things have done wonders for gaining new energy and perspective with my work: getting into the wilderness and getting onto the dance floor. For me at least, these are the cheapest and most effective forms of career therapy going. Allowing myself a few extended, well-timed trips to the woods have sufficiently cleared my head and helped me to sharpen my resolve about work and vision. There is a kind of advice that I need about my work that only high mountain ridges and marmots can give. In the past, I’ve found myself saying “I can’t afford the time or money” but neither activity is really that expensive and I figure I’d spend far more energy on the stress that accumulates from abstaining. In other words, I can’t afford not to do it.

“Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit.” – Edward Abbey

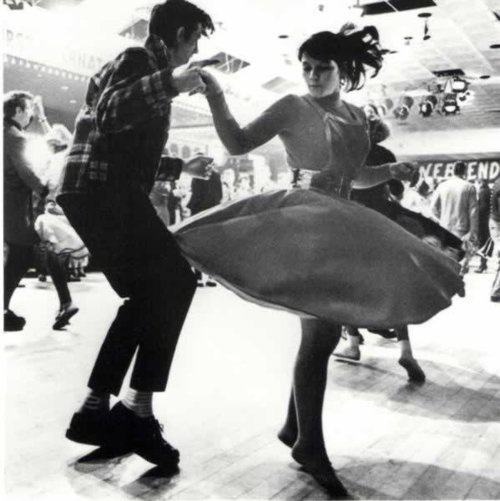

Once back in the city, I’ve relied on another (non-practice) practice that has been profound in rearranging my musical molecules: partner dancing. In this case, what the kids are calling fusion and blues. But any style would do it. Here’s the thing: there is a point at which musicians can’t get any better at music by “hearing harder.” There needs to be space. You see it in nearly every genre. Pickers get on this self-referential feedback loop. It ends up being all about the material. The stuff. The minutia. The A augs and the G#m7b5s. The gear. Not the feel. The tone of voice. The connection. Music is such a shared experience. As I have said many times before, ideally, we get out of our heads long enough to realize that the experience is not just between fellow geeks, but everybody in the room. Nowhere have I felt this more clearly as when I crawl out of the woodshed, step off the stage and out onto the floor. The connection with my partner becomes by extension, a connection with the entire room and my whole auditory world. For me, this is when the music can really get in there. Uninterrupted. I can feel and hear the groove, melody and lyrics in a more relaxed, expansive and peripheral way and it reminds me of my best moments performing. I’m just feeling it and it’s happening.

“Music begins to atrophy when it departs too far from the dance.” – Ezra Pound

In this state, I like to think of the sound as not coming in just through the front door – e.g. when we decide to let it in – but more like an easy breeze through multiple windows. One window could be eye contact with your partner or a grin while the chorus or horn section rolls by, another might be a dip, a swing on the kick or the high hat. Here is where you become both the mover and the one being moved. Concurrently. And subtly, even imperceptibly blending those two roles is what, in my view, makes for great music. And dancing. And life.

I highly encourage all my friends, fans and students to try to recognize when they are intractably stuck. Then respond, not by tweaking or fixing the situation, but rather by just consciously stopping. This is when walking away is actually stepping up. Put down the instrument and “get outa Dodge.” Ask someone to dance. Practice non-practice. If we can’t be present outside the workshop, we will never be fully present when we get back.

So I’m back to work now and thrilled about a very new direction with my music.

Hint: you can dance to it.